From Sheperd Paine: The Life and Work of a Master Military Modeler and Historian by Jim DeRogatis (Schiffer Books, 2008)

J.D. You did start simply yourself, in terms of a pretty simple setting and straightforward story: “The Idylls of a Voltigeur.”

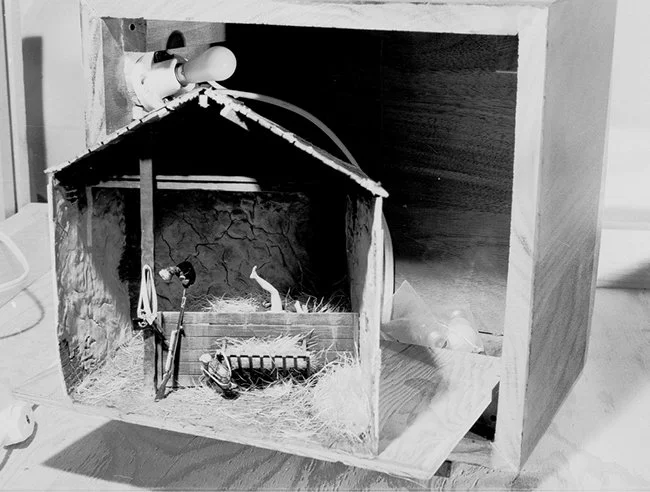

S.P. That was just because I had an idea for a scene, and of course, the reason you do a box is because you want to restrict the viewpoint. This was an indoor scene, in a stable, and, of course, the whole idea of “The Idylls of a Voltigeur” is you never see the girl—all you see is her leg sticking up from behind the partition. So it was important to restrict the viewpoint. That was a very simple box, lit by a single light bulb, and it was 54mm, so it was small.

I learned a lot about boxes from that, because it was my first experience dealing with timing: Viewers should look in and not be sure what is going on at first. Then it gradually dawns on them, and that’s where the laugh comes.

J.D. I enjoy how you used just a couple of clues—the woman’s leg, the French soldier’s equipment hanging on the post—to tell the story. Did you model the rest of the voltigeur and his paramour, the parts we can’t see?

S.P. Yes, though I’m not sure how much I ended up doing detailed painting on. I did just enough to make sure that you couldn’t get around to a different angle and see something you weren’t supposed to see. The woman was all there; that was the mounted Historex figure of Lady Godiva, so she was ready to go, complete with her legs in the appropriate position!

After that, I didn’t do another box for five or six years. I was still primarily interested in Historex, and of course, “The Idylls of a Voltigeur” was a Historex piece.