We all are familiar with shoebox dioramas from grammar school, but this Web site is devoted to looking at the box diorama as art, as practiced by many in the field of military miniatures and figure sculpting and painting, and as first widely popularized by master modeler Sheperd Paine, whose work you will find in ample evidence and whose example and wisdom will often be invoked in the pages of this Web site.

Shep contends that boxed dioramas represent the pinnacle of a modeler’s skills, and his evince a deep knowledge of history; exquisite design; incredible sculpting; ingenious scale modeling; vibrant painting, and dramatic lighting, as well as the most important ingredient: gripping story-telling. Simply put, they are as close as we are every likely to come to the fantasy of a time machine, enabling us to step back, if only for a moment, to watch as history unfolds, albeit in a stop-time moment.

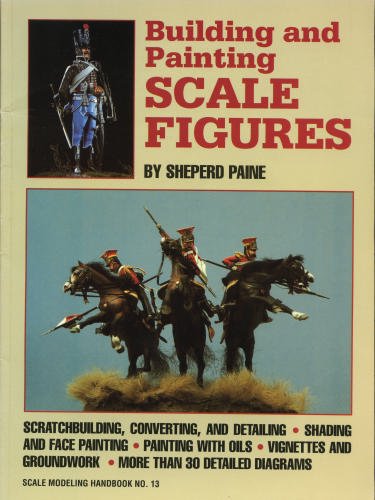

The twenty-five boxed scenes that Shep built during his modeling career remain some of the most famous dioramas a miniaturist ever has produced, and you can see them on his gallery page here. Many other modelers have followed in his footsteps, however, and you can see their work, too. Some of them still are active today (and are eager to see other modelers try their hand at making a box diorama), and some have retired, permanently or for an indefinite hiatus. All of them hold Shep’s work in high esteem, however, so it’s worth hearing some of Shep’s thoughts on the form as an introduction to this site and this aspect of the hobby. These comments are taken from the chapter on his boxes in Sheperd Paine: The Life and Work of a Master Modeler and Military Historian by Jim DeRogatis, a book any box diorama maker or enthusiast will want to own, along with the two of Shep’s four how-to books most useful to this pursuit, How to Build Dioramas and Building and Painting Scale Figures (the first remains incredibly popular around the world, but the second sadly is out of print).

SHEPERD PAINE: “There’s a mistaken impression that I invented the boxed diorama, but that is just not true. Boxed dioramas were a poplar feature in museums long before I was born, and of course, everybody had to build a shoebox diorama in grammar school.

“There was also a man named Theodore Pitman in the 1930s whose company built some very good historical boxes in Massachusetts. Some of them are at Harvard University, and some are in the war memorial at the Newton Town Hall. I hadn’t seen any of these at the time I started, but his work was impressive. The figures were larger than mine—about six inches high—and they remain some of the best museum dioramas I have seen. He did some fairly well-known subjects: the fortifications at Bunker Hill; Pickett’s charge at Gettysburg; a World War I battle scene; the siege of the Alamo; a very good depiction of the spar deck of the Constitution in battle, and a nice scene of Washington at Valley Forge. So this is an old tradition; it’s hardly something that I invented.

Theodore Pitman’s 1952 Alamo diorama.

A Pitman diorama entitled Camp Disaster, Shadagee Falls, Dead River, Maine, 1775.

“I think the first two boxed dioramas I ever saw were at the Philadelphia (Miniature Figure Collectors of America) show the first year that I went, either in 1968 or ’69. One was by Ray Anderson, who was the leading maker of boxed dioramas at the time; I think it was The Casting of the Liberty Bell. The other box that I found particularly intriguing was one that the Military Collectors of New England did of the assault on Bunker Hill, based on the famous Howard Pyle painting. They’d done it all in 54mm figures, but they had put a small opening on the front of the box and used a reducing glass on it, so that when you looked through the reducing glass, they looked like the most beautifully detailed 30mm figures you ever saw. The only problem was that it resulted in a fairly large box with a very small opening, but the idea was still very clever. I think Henri Lion was the creative mind behind that one.

“I think that since Bill Horan and Mike Blank brought their boxes to the World Expo in Boston in 2005, we might start seeing a resurgence of box dioramas again. And Nick Infield and Dennis Levy are both doing interesting boxes. Some people are daunted by the woodworking, but it’s not as hard as you think. When I was living in an apartment, I didn’t have the facilities to do that kind of carpentry work, so a friend of mine, Ron Hillman, built the actual boxes for me. Later on, when I moved into a house, I built the boxes myself, but you can always get someone to help you with that stuff if you need to. Besides, if people are looking at the outside of the box, that means you really haven’t done your job with the inside! But neither the woodworking nor the lighting is really that hard.

“I’ve always said that the hardest part of doing a boxed diorama—and this applies to any diorama, but it’s especially true of boxes—is the planning: getting the composition and the design set to the point where you’re effectively telling the story. Recently at a show in Canada, I met a guy who had done a boxed diorama, and he asked me for some criticism. I told him, ‘This is good and this is good,’ and I made a few suggestions for improvements. A photographer friend who was there overheard this and later sent me an e-mail saying, ‘I’m interested in the way you criticized that man’s work, because you were saying things about composition and design, and in model work you don’t hear that very often.’ I wrote back and told him that’s too bad, because those really are the most important factors.

Anderson's 1994 BOOK, THE ART OF THE DIORAMA, ALSO IS INCREDIBLY HELPFUL TO BOX DIORAMA MAKERS, THOUGH IT IS SADLY OUT OF PRINT.

Ray Anderson working on a box diorama paying tribute to his recurring themes and characters.

“I’ve seen so many dioramas that failed before they even started, because they hadn’t been properly designed. The design and the composition—what you decide to tell, and what you decide to leave out—those are the most important things. In some ways, dioramas are so interesting because you are telling a story without words. It’s like silent movies, except that the actors aren’t even moving.”