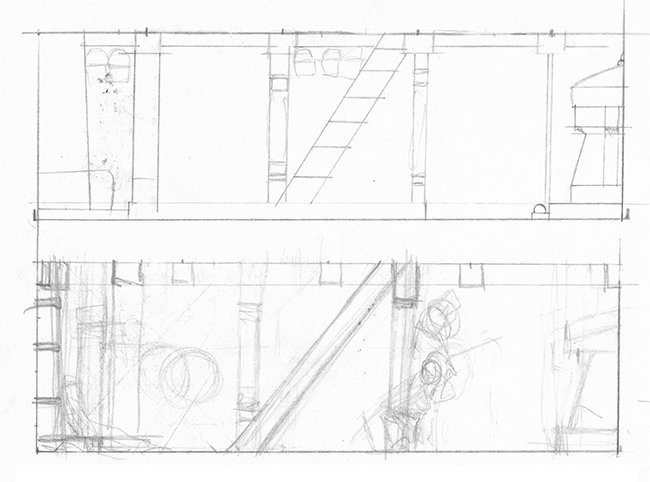

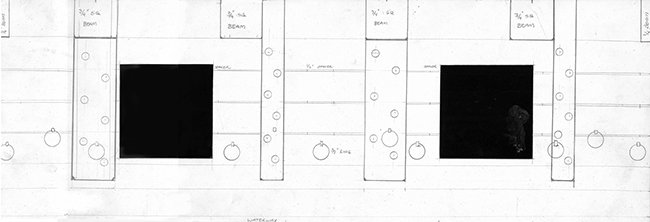

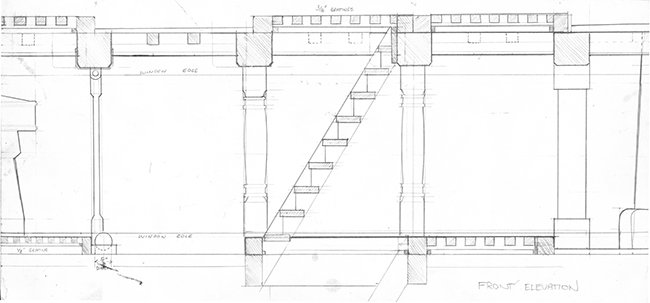

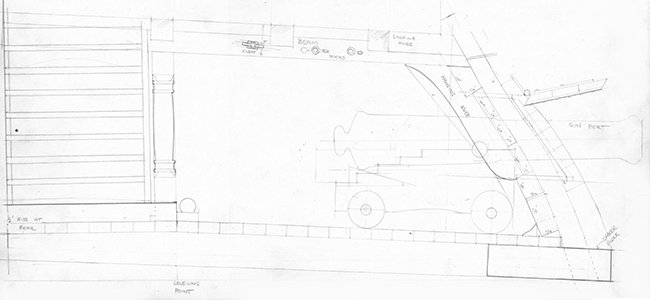

Above: Shep’s plans for this ambitious diorama, and some shots of the work in progress. Below: Detail shots from the diorama.

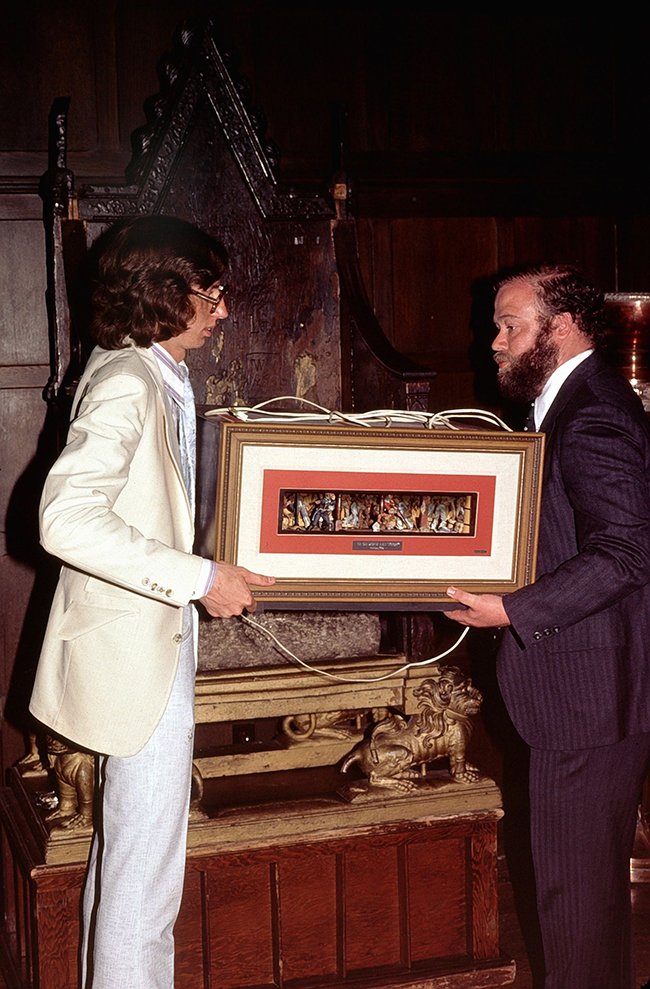

Above: Joe Berton writes, “The Victory shot was taken at Casa Loma, in Toronto, for the Ontario Model Soldier Society show. Casa Loma was a wonderful location for a figure show. It was a Victorian built castle, filled with all kinds of splendor: suits of armor, dark dining halls, outdoor balconies and gargoyles. We are placing the box on the duplicate Coronation Chair that even had a replica Stone of Destiny under it. We thought that was so cool.”

SHEP’S NOTES ON THE DIORAMA

Naval battles during the age of sail were generally brief and bloody affairs. The Battle of Trafalgar was decided in scarcely three hours of concentrated havoc, during which one ship blew up and forty-two others were reduced to barely manageable hulks. The destructive power of a ship of the line during this time was truly awesome. A man-of-war the size of HMS Victory could throw out a broadside of more than half a ton of iron shot and could do so at a sustained rate of two or even three broadsides per minute. Visualize two such ships lashed side-by-side and firing into each other at this rate for an hour or more and you begin to get some idea of the violence of a naval battle of this period.

Nowhere was the raging tumult as concentrated as on the gun decks. The noise level alone was incredible; the volume of sound and the concussion created by thirty guns, each more than twice the size of the largest fieldpiece used on land, going off in a confined space, with guns of similar size firing on the decks immediately above and below, staggers the imagination. Add to this the powerful recoiling of the guns, the crash of enemy shot coming through the ship’s wooden sides, and the agonized screams of the maimed and dying, and one can begin to comprehend what the experience must have been like. If there was ever a hell on earth, it was the gun deck of a sailing man-of-war at the height of a battle.

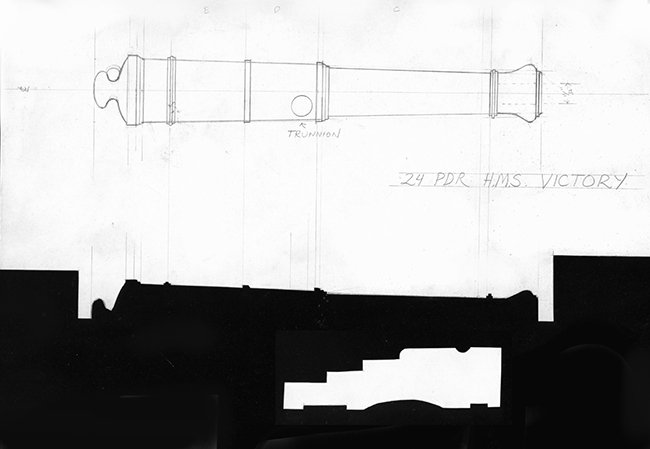

The most common naval gun at Trafalgar was the twenty-four pounder, found on the middle gun deck of HMS Victory. The barrel alone weighed almost three tons and it took a crew of eight strong men to load and fire it. Loading was a long, involved, and dangerous process, further complicated by the unpredictable roll of the ship. Nonetheless, a well-trained crew could maintain a rate of as many as three shots per minute.

Firing was usually by means of a flintlock and lanyard mounted on the gun, though traditional rope matches were kept ready should the lock fail. The heavy breaching rope around the back of the gun was secured to the ship’s sides and restrained the recoil. As the guns grew hotter from repeated firings, they recoiled even more forcefully, leaping not only backward but up off the deck as well. On a crowded deck in the heat of battle, accidental injury and death were commonplace.

Though the warships of this time were built of wood, they could absorb an amazing amount of punishment. It was extremely rare for a man-of-war to be sunk by gunfire. The sides of warships were much sturdier than those of merchantmen; the frames were spaced less than four inches apart and, with the inner and outer planking, offered a barrier of laminated cross-grained oak fully two feet thick.

Yet even this two-foot thickness of solid oak could be penetrated by a twenty-four-pound round shot at a range of a thousand yards. And while the shot itself was deadly enough, it was actually the splinters caused as it burst through the ship’s side that caused the majority of casualties. These splinters were often more than three feet long and, propelled with sufficient force to skewer a man through the chest, could inflict ghastly wounds. To reduce the danger from splinters, everything made of wood not actually needed to fight the ship

Naval battles during the age of sail were generally brief and bloody affairs. The Battle of Trafalgar was decided in scarcely three hours of concentrated havoc, during which one ship blew up and forty-two others were reduced to barely manageable hulks. The destructive power of a ship of the line during this time was truly awesome. A man-of-war the size of HMS Victory could throw out a broadside of more than half a ton of iron shot and could do so at a sustained rate of two or even three broadsides per minute. Visualize two such ships lashed side-by-side and firing into each other at this rate for an hour or more and you begin to get some idea of the violence of a naval battle of this period.

Nowhere was the raging tumult as concentrated as on the gun decks. The noise level alone was incredible; the volume of sound and the concussion created by thirty guns, each more than twice the size of the largest fieldpiece used on land, going off in a confined space, with guns of similar size firing on the decks immediately above and below, staggers the imagination. Add to this the powerful recoiling of the guns, the crash of enemy shot coming through the ship’s wooden sides, and the agonized screams of the maimed and dying, and one can begin to comprehend what the experience must have been like. If there was ever a hell on earth, it was the gun deck of a sailing man-of-war at the height of a battle.

The most common naval gun at Trafalgar was the twenty-four-pounder, found on the middle gun deck of HMS Victory. The barrel alone weighed almost three tons and it took a crew of eight strong men to load and fire it. Loading was a long, involved, and dangerous process, further complicated by the unpredictable roll of the ship. Nonetheless, a well-trained crew could maintain a rate of as many as three shots per minute.

Firing was usually by means of a flintlock and lanyard mounted on the gun, though traditional rope matches were kept ready should the lock fail. The heavy breaching rope around the back of the gun was secured to the ship’s sides and restrained the recoil. As the guns grew hotter from repeated firings, they recoiled even more forcefully, leaping not only backward but up off the deck as well. On a crowded deck in the heat of battle, accidental injury and death were commonplace.

Though the warships of this time were built of wood, they could absorb an amazing amount of punishment. It was extremely rare for a man-of-war to be sunk by gunfire. The sides of warships were much sturdier than those of merchantmen; the frames were spaced less than four inches apart and, with the inner and outer planking, offered a barrier of laminated cross-grained oak fully two feet thick.

Yet even this two foot thickness of solid oak could be penetrated by a twenty-four pound round shot at a range of a thousand yards. And while the shot itself was deadly enough, it was actually the splinters caused as it burst through the ship’s side that caused the majority of casualties. These splinters were often more than three feet long and, propelled with sufficient force to skewer a man through the chest, could inflict ghastly wounds. To reduce the danger from splinters, everything made of wood not actually needed to fight the ship—furniture, bulkheads, etc.—was either taken below or simply thrown overboard when the ship was cleared for action. These deadly splinters were also the reason oak was used for the construction of warships even long after teak had been found to be more seaworthy: teak wounds often led to gangrene and death, while oak wounds were almost always clean.

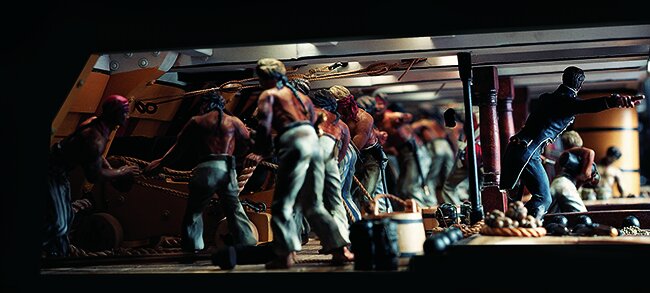

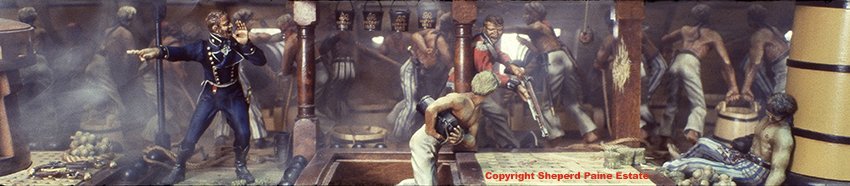

The diorama depicts the middle gun deck of HMS Victory at the height of her battle with the Redoubtable. This section of the ship was commonly known as the “slaughterhouse” because of the heavy casualties sustained there. In the foreground of the scene can be seen the lieutenant commanding this part of the deck. Behind him, the gun crews are loading and firing as fast as they can. One crew has finished loading and is straining at the tackle to steady the gun against the ship’s roll while the gun captain primes the lock with powder before firing. The crew to their right is at about the same stage (the gun captain is about to clear the vent with the vent pick in his hand), but the men have stopped to remove a casualty. The men are stripped to the waist, not only for comfort in the heat, but also so that shreds of cloth from their shirts will not be driven into their wounds should they be hit. Most have neckerchiefs around their heads, partly to keep sweat from their eyes, but primarily to protect their ears from the deafening sound of the guns. The decks are sprinkled with sand and the men are barefoot to give them better footing on planks slippery with blood. It had been customary to paint ships’ interiors dark red so blood would be less evident but the Royal Navy abandoned this practice in 1797.

Scattered about the deck are the implements necessary to serve the guns—sponges, rammers, ladles, fresh and salt water tubs, etc. Rope wads were used to pack powder in the barrel and to keep the shot from rolling out of the guns before they were fired. The most common type of shot for close range was grapeshot and stocks of these can be seen in shot garlands on the deck. Half of each gun’s crew was assigned to the ship’s boarding party and these men wear pistols and cutlasses.

Marines were stationed at all companionways with orders to shoot anyone who tried to take refuge below. Only the powder monkeys were permitted to pass. These boys, sometimes less than ten years old, acted as runners, carrying powder up to the guns from the magazines deep in the ship’s bowels. The frantic nature of their job is reflected in the fact that in a general action such as Trafalgar, a ship of Victory’s size could bum up more than five hundred pounds of black powder every minute.

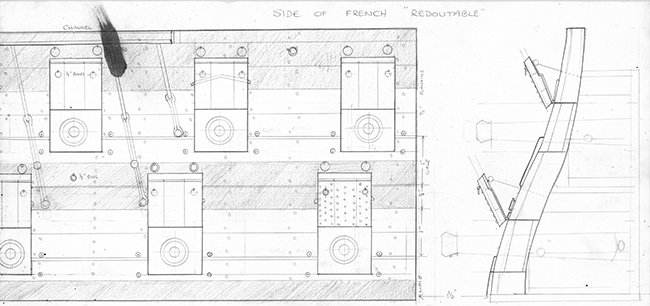

Visible through the gunports is the French Redoubtable. It was from her mizzen top that a French marksman felled Lord Nelson early in the battle. Mounting the standard seventy-four guns to Victory’s one hundred and four, she was badly outgunned by the larger English ship. Nevertheless, she fought it out blow-for-blow for more than an hour, crippling the British flagship so badly that she had to be towed back to Gibraltar. Only when the British Temeraire, with ninety-eight guns, came along her other side and both British ships started firing into her simultaneously did the gallant French ship finally strike her colors. By this time, she was completely dismasted, most of her guns were dismounted, and nearly five hundred men, better than half her crew, lay dead and dying on her decks.

Research for this diorama, while extensive, was not especially difficult. Naval practices during the Trafalgar period are fairly well documented. HMS Victory is preserved in her Trafalgar appearance at Portsmouth and there are sufficient memoirs, ships’ logs, and order books extant to accurately reconstruct life on board. Nearly all the information required was contained in four books, each a classic in its own right. These were the primary basis for the planning and construction of the diorama: Sea Life in Nelson’s Time by John Masefield; The Anatomy of Nelson’s Ships by Nepean Longridge; Le Vaisseau de 74 Canons (four volumes) by Jean Boudriot; HMS “ Victory”: Building, Reconstruction, and Repair, 1765-1965 (two volumes) by A. R. Bugler.

From Sheperd Paine: The Life and Work of a Master Military Modeler and Historian by Jim DeRogatis (Schiffer Books, 2008)

J.D. The Rorke’s Drift scene and “In the Turret of the Monitor” both won Best of Show prizes, one at the MFCA in Philadelphia and the other at the MMSI in Chicago, but you were just warming up, because your next project was “The Gun Deck of the HMS Victory at Trafalgar, 1805.”

S.P. I learned from the Monitor that I could scratchbuild the mechanics for a scene like that; the part that had me worried was turning the Dahlgren gun barrels, which I did with wood on a small lathe. That gave me the confidence to tackle the Victory.

The Victory was a project that sort of grew. The cornerstone of the concept was using the mirrors at each end. Again, I won’t lay claim to being the first guy to use mirrors for models: I got the idea from John Allen, the model railroader, who made a huge underground parking garage on his layout using four mirrors and two cars, so that when you looked into the doorway, the cars extended forever in all directions. He also used mirrors in his layout for other things, to get an additional sense of depth and so on. John and his Gorre & Daphetid were a great inspiration to me, and the book Kalmbach published on his layout is still one of my favorites.

I’ve always been fascinated by the Victory. I’d visited the ship as a boy—I’d always been interested in ships and I was fascinated by the Nelson period—but by that time, I had already done the ship models for Valiant, so that I’d finally gotten model ships out of my system.

J.D. Nobody else was really doing the interiors of these ships, which was where much of the action and drama were. Modelers always model the decks and sails.

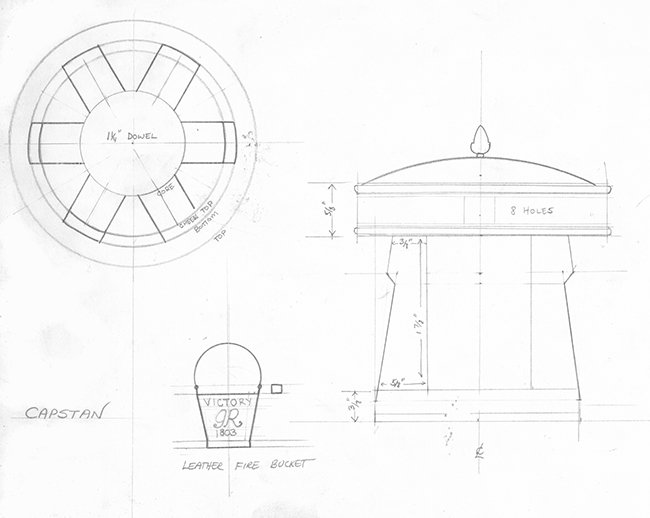

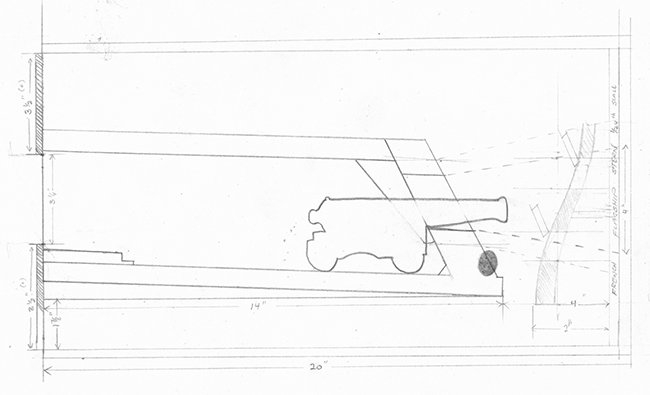

S.P. Yeah, and they spend most of their time tying tiny knots in the rigging! But there were sightline problems with a scene on the spar deck; sightlines are a constant problem in box dioramas, and if you can’t solve them, it’s better not to do the scene at all. Exterior scenes need a painted background, and unless you are a lot better than I was, painted backgrounds always look like painted backgrounds. I really liked the confined space of the lower deck, although this is actually the middle gun deck. I did a lot of research, and the reason I chose the middle deck is it had a bit more overhead, and I could use the mast and the capstan to mask the mirrors at each end. The lower deck didn’t have a capstan on it.

I did a lot of drawings in preparation for the Victory, most of them in the same scale as the model. I’d done some drawings for the Monitor, but they weren’t nearly as detailed as the ones for the Victory. All I had to do later was to cut out the pieces and lay them on the drawing to make sure they were the right size.

J.D. I love the text that you wrote to accompany this scene, which is on display along with the diorama in the Forbes Collection in New York City, and the way the box itself drives home the terror of working on that deck: Shells are hitting the ship; shrapnel and wooden splinters the size of a man’s arm are flying around; it’s hot, it’s noisy, it’s loud, and the marine is going to shoot you if you’re not doing your job… these sailors were screwed ten times over!

S.P. Yeah, that pretty much describes it. I’ll tell you a great background story: In some of the pictures, you can see the splintered side of the ship. When I first started building the deck, I started with the big wooden beams overhead. I hadn’t gotten much further when a friend of mine came to visit and brought his dog with him, and while we were drinking beer in the living room, the dog was in the studio, chewing on the beams! The beams were ruined, of course, but when it came time to put the splinters into the side of the ship, the dog made far better splinters then I ever could have: They were much more random and more finely detailed! So that was the dog’s contribution to the diorama.

J.D. The intact woodwork on the deck and all of the fittings is really impressive.

S.P. The wood is mostly maple, because it’s a good, hard wood, and it takes a sharp detail when you turn it; it was just stained to look darker, like oak. Most of the pillars were turned on a Dremel lathe. To get all of the pillars alike, I made a cardboard template, which I could constantly hold next to the work to ensure that it matched. The gratings overhead were made like real gratings: The crosspieces were all dovetailed into each other. I had done a certain amount of woodworking with the Monitor; this was obviously a lot more, but I had been associating with ship modelers for a long time, so I had the benefit of their advice and their experience. I was working with much bigger pieces of wood than they usually work with; they’re usually working with very, very small strips. Here, as I recall, the planks on the side of the ship are close to a quarter of an inch thick.

J.D. Again, the detail is amazing: You’ve got the cannon balls lined up; the grapeshot; the water buckets with resin water in them. What are those larger buckets?

S.P. The guns were actually fired by flintlocks, but they kept old-fashioned lit matches handy in case the flintlocks failed. These were kept in notches around the edge of a tub, with the lit end over the water, so that if anything happened, they’d fall into the water and be extinguished. The greatest fear in those days was fire onboard, not only because it was a wooden ship, but also because it was a wooden ship full of gunpowder. There were a number of unfortunate incidents where ships blew up in the middle of a battle.

J.D. Ninety-nine out of one hundred people looking at the box probably have no idea what those tubs were, but it was important to you to model them?

S.P. A lot of the fun was doing the research, and then putting all that research into the scene. Things like the match tubs were done as much for my own satisfaction as for the audience. Every so often, somebody would come along who really knew the period, and he’d pick up on all of those things. So you have the shot garlands, the grapeshot, and the wads, which were actually made of yarn and were used to keep the cannonballs from rolling out of the barrel as the ship pitched in the sea.

Again, as I did with Rorke’s Drift, I added more sculpted pieces with every box diorama. Remember, I still had access to the casting equipment at Valiant. So I’d make one Martini-Henry rifle, using a piece of metal tubing for the barrel and epoxy putty for the other parts, and then cast up a bunch of them in white metal. When I got to the Victory, the cast pieces were things like the shot wads, fire buckets, pistols, cutlasses—just about anything that was repetitive was cast. I added some more sailors, heads in bandanas, and quite a few other pieces, too.

J.D. How did you illuminate this one?

S.P. This one I had to cheat on, because the overhead was solid, and I didn’t want the scene to be too dark. I actually had to cut some holes in the overhead behind the beams and sneak some light through from there. I had not learned about doing miniature spotlights yet. but even today, I don’t think I would have been able to do it with spotlights, and I’d still have to cheat a bit. You wouldn’t have been able to see much at all if I’d left the lighting the way it really would have been, because the only light was coming through the gun ports. It was pretty dark down there.

J.D. How did you come up with the idea of showing a glimpse of one of the French ships through the gun ports?

S.P. As I said, backgrounds can be tricky. For the Monitor, I snapped a photograph on the shore of Lake Michigan and pasted it to a curved backdrop behind the gun port, so if you took the trouble to look through the gun port, you’d see water and a horizon. With the gun ports on the Victory, I realized you’d see something more, so I came up with the idea of putting the French Redoutable on the other side.

Midway through the project, I became intrigued with the idea of actually putting motion into the box. To add motion to the Victory, I realized that all I had to do was hinge it at the back and use an electric motor with a counterweighted pulley system to raise and lower the back of the deck. Then, I realized I could have both ships moving. If the Victory was moving up and down, the French ship could rock from side to side. The result is that when you look into the scene, the combination of the different motions gives an eerie, floating sensation.

The problem with putting motion in the scene is that it draws attention to the fact that the figures are not moving. I was very concerned about this, so I made sure that there was a separate on/off switch for the motion, because if it didn’t work, I could simply leave the switch off, and nobody would know the difference. I finally decided that the motion would work, though, because it is really part of the setting, and if it was slow enough that people didn’t immediately realize that the deck was moving, it became a tromp-l’oeuil[1] effect. The reaction to this was better than I had hoped for. At shows, people would look at the diorama for a couple of minutes, and then, all of the sudden, their eyes would widen and they’d mutter, “My God, it’s moving!” That was the neatest part: It took that long for them to become aware of it, and even then they wondered if their eyes weren’t deceiving them.

J.D. You love that sort of reaction. It was a goal of most of your boxes, wasn’t it?

S.P. Not necessarily, but it’s always fun to have something there for a delayed reaction. Dioramas are a form of entertainment, and it’s important to entertain people beyond the initial few seconds of looking into the box. There have to be new things for the viewer to discover. One of the ways to measure the success of the box is how much people’s heads are bobbing in front of it, because they’re discovering things in corners and hidden behind things as they look through the window.

J.D. When I saw this box on display at the Forbes Galleries[2], I noticed two well-worn spots on the wall on either side, where people obviously had put their hands as they leaned to stare into the opening. Quite a compliment! Tell me about the trick with the guy you cut in half.

S.P. I didn’t cut the guy in half; I cut the bucket in half, and his reflection is carrying the other half of the bucket. That worked out far better than I ever hoped it would. On another figure, I did a backwards tattoo, just for the fun of it. I realized you weren’t going to see much of the figure, but his reflection would be visible. I painted it backwards, so that it would read correctly in the reflection. However, I played it safe—the ship’s name I wrote backwards was “Ajax,” not “Agamemnon!”

J.D. You’ve made a point when talking about the Monitor of saying that everything was scratchbuilt, except for a water tub, which was a Historex wine cask cut in half.

S.P. With the Monitor, I didn’t think I could build a decent bucket, but by the time I got to the Victory, I’d learned how to build buckets. With the Monitor, I still had one or two apron strings tied to Historex; by the Victory, everything was scratchbuilt, with no commercial parts used of any kind.

J.D. When this one was completed, Malcolm Forbes got his revenge on Ralph Koebbeman for losing out on the Monitor, right?

S.P. Malcolm didn’t really get his revenge, but in a moment of weakness, I promised him the Victory because he didn’t get the Monitor. Looking back, I’d much rather have sold it to Ralph. The problem with selling to Malcolm Forbes was that it was simply his latest purchase—there’d be another one later that afternoon—whereas it represented four months’ work on my part. With Forbes, it was sort of like holding something up in front of a vacuum cleaner: One moment it’s there, and “Whoosh!,” the next moment, it’s gone. To me, it’s not how important people are, it’s the enthusiasm they bring to collecting. Ralph Koebbeman and the Wyeths made it clear how much they enjoyed having the pieces, and that was in many ways more gratifying than the money.

J.D. You enjoyed getting to know the people who bought your work. Did you ever even meet Forbes?

S.P. No. I talked to him on the phone a few times, but we never met in person.

[1] From the French: “deceive the eye.” Shep: “Think of when they paint the sides of buildings so it looks like there’s architectural detail that isn’t really there.”

[2] Located on the first floor of the Forbes magazine offices in Greenwich Village, New York, the Forbes Galleries were open to the public for free viewing for years, until the publisher’s death. Dan Bird originally bought the Victory at auction when the galleries were liquidated. After his death, it was purchased by collector Bill Neustadt.