Above: Shep’s guide to the personalities in the scene, some of his planning drawings, and in-prorgess shots of the cabin. Below: Details from the diorama.

SHEP’S NOTES ON THE DIORAMA

This is another of those subjects I’ve wanted to do for some years. The elegance of the Admiral’s cabin, with its candlelight, fine silver, and vintage port form such a lovely contrast to the harsh realities of the gun deck.

The original concept of the scene was to do Nelson’s last supper with his officers on the eve of Trafalgar, that being a more significant and moving occasion. But there were historical difficulties: there proved to be suspiciously little information on Nelson’s pre-Trafalgar dinner, certainly in occasion that anyone present would be likely to remember and write about in later years. Yet there was only a very brief description by a midshipmen quoted in one or two accounts, and these were not attributed to a specific source. Moreover, naval officers operated on nautical time and ate dinner at three in the afternoon, which would eliminate the need for candlelight, an essential “atmosphere” ingredient in the scene. As a result, I was unsure of the direction the project should take until I received a letter from a noted naval historian who expressed doubt that the dinner ever took place, an opinion that convinced me that whatever dinner I chose, the occasion should not be Trafalgar.

Fortunately, an alternative was readily at hand. Such a dinner did take place on the eve of the battle of Copenhagen, a less inspiring occasion, to be sure, but one for which the entire affair was well-documented as to time, place, officers present, etc. I therefore resolved to transfer the subject to this event. The fleet anchored late and the officers having been too occupied during the today to dine, Nelson invited a group to his cabin that evening. From a diorama standpoint, the setting on board his contemporary flagship HMS Elephant, was even better than the Victory, where the admiral’s dining cabin was totally enclosed; on the smaller Elephant, the cabin opened onto the stern windows, where the lights of the city of Copenhagen could be seen flickering in the dark.

Most of the officers present are known (a few educated guesses filled out the rest of the group) and the figures of them are based whenever possible upon contemporary portraits. They were a young and distinguished company. Foley of the Elephant was the oldest man present at 44 (Nelson was 42); the rest were in their thirties. Sir Walter Thompson, 31, had been knighted for a desperate ship-to-ship action two years before, but his luck ran out of Copenhagen, where he would lose a leg to a cannon ball. Edward Riou was generally regarded as the finest frigate captain in the Royal Navy and would play a crucial part in the battle before being killed on his own quarterdeck at the end of the action. Captain Hardy (at 32, younger than commonly supposed) had enjoyed a meteoric rise as Nelson’s close friend and protégé; not even a captain at the Nile, three years later at Copenhagen he was Nelson’s flag captain in the St. George, a 98 gun three-decker (Nelson transferred his flag to the shallower draft Elephant so he could be closer to the action).

Beyond finding portraits and visual descriptions of the participants, research was not a problem. The technical aspects of the ships of the period are fairly well-documented. Although minor details of common practice of dining at sea raised some questions, these were fortunately negated by the fact that the toasts were usually drunk at the end of the meal after the table was cleared and before the fruit, cheese, and nuts were served (this being spring in the Baltic, the fruits were omitted). I left the dirty dishes visible behind a cannon a) because they show off the elegance of the silver service and the chest in which they were stored b) because that was a logical place for the servants to put them and c) because they added a nice touch of human interest to the scene. The cheese was Stilton and the nuts walnuts.

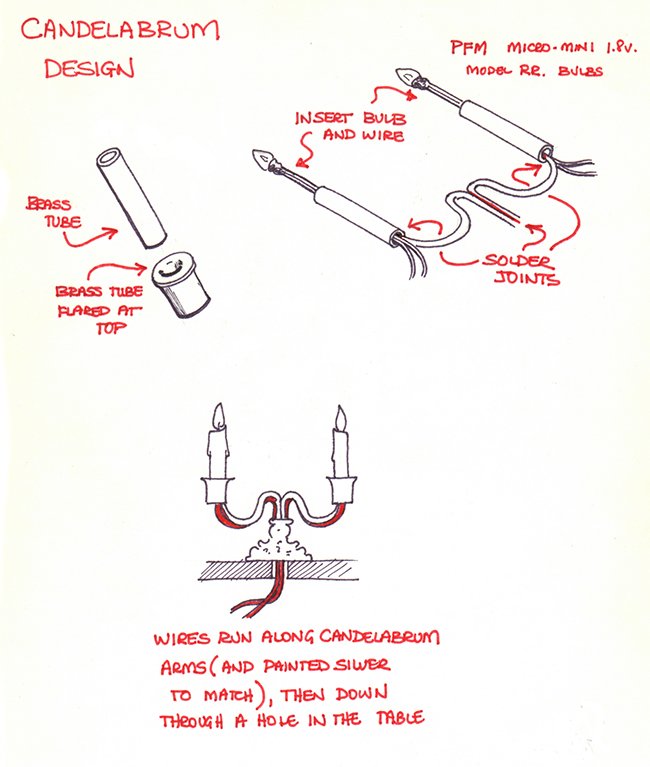

Details of the cabin itself are based upon contemporary descriptions and the Captain’s cabin on HMS Victory. Technically, this was the most difficult feature of the construction, since I had never built anything this elegant from scratch before. The tables chairs and other furnishings had to be of a quality suitable for a high-ranking naval officer and the silver had to gleam properly in a candlelight. The cabin itself was also a challenge. The walls were elegantly paneled and trimmed in gold. The floor was covered with canvas painted in the checkerboard pattern to simulate tile (I used cardboard, and carefully masked and painted the tiles).

Much of the elegance of the scene derives from the graceful arc of the stern windows across the back of the cabin. These windows curve both upward and outboard in a sweep across the stern, with a result that no two windows or two panes within those windows are exactly alike. Each window therefore had to be constructed individually, piece by piece: 28 separate strips of wood were required for each window. each piece being cut and custom fit into its place. Two windows are open for ventilation; because of the tapered shape of the window, they were hinged at the top top and supported on cords from the overhead. Attention to little details like this (and the wine stored in the bench seats under the windows) are what make a setting look “lived in” and natural, important factors in the mood and realism of a diorama.

The cannon in the cabin provides an incongruous and warlike touch to the scene: a grim reminder, perhaps, of the battle to follow. This is no flight of fancy; it was standard practice at the time. Every inch of space on board was devoted to the ship’s purpose as a fighting vessel, and in action the captain’s cabin was completely dismantled to give the crews room to work the guns.

The portrait of Lady Hamilton is one Nelson always took to sea.

The figure of Nelson was difficult, partly because the portraits of him vary so much and also because none of them show him smiling. As my primary source I used the wax effigy in Westminster Abbey which was modeled from life and was said by Lady Hamilton to be the best likeness. The bemused smile is something of a guess, but is important in setting the mood of confident anticipation for the battle the following day.

The real subject of this diorama is the special relationship that existed between Nelson’s commanders. Nelson’s famous comment that he looked on his captains as a “band of brothers” was no idle boast; there was a tie of friendship, loyalty, and even love between these men that was both subtle and deep. The dinner on the eve of Copenhagen was clearly a special occasion of great emotional import, a last meeting of friends and a mustering of that feeling to support them through the trials of the battle the next day. Many of those present were old friends of the Admiral, brought together once more by the demands of war. Each was aware that some of those present would not survive the next day, and this dinner was a celebration of the bond that had grown between them.

From Sheperd Paine: The Life and Work of a Master Military Modeler and Historian by Jim DeRogatis (Schiffer Books, 2008)

J.D. That is a great story. Where did you get the idea for your next box: “To a Fair Wind… and Victory!”?

S.P. What I originally wanted to do was Nelson and his captains having dinner on the eve of Trafalgar. Unfortunately, Nelson dined alone on the eve of Trafalgar—damned uncooperative of him, I must say—but I knew that the evening before the Battle of Copenhagen, Nelson did host a dinner for all of his captains. The interesting thing about it is that there were a number of army units serving as marines on board, and some of the Army officers were also present at the dinner. Colonel Stewart of the Rifle Brigade left a detailed account of the occasion, and you can see him in the left foreground.

J.D. So this is set in Nelson’s quarters?

S.P. Yes, the admiral’s quarters on HMS Elephant.

J.D. Nice digs!

S.P. Admirals lived well

HMS Elephant was only a seventy-four, not a hundred-gun ship. I had good reference material—a lot of photographs and such from HMS Victory, which showed the English style of furnishings. There’s also a very fine book by Jean Boudriot, The Seventy-Four Gun Ship, which is four volumes full of very detailed drawings. It’s a marvelous book—one of the definitive works on the subject. If you had all four volumes, you could not only build the ship, you could outfit it right down to the chaplain’s communion set, which is illustrated, and the final volume tells you how to sail it. I originally bought it in French, thinking that there would never be an English version, but sure enough, about five years later, someone published an English edition.

J.D. I love the fact that even in these beautiful quarters, there’s still a cannon.

S.P. That was standard practice. When they cleared the ship for action, they removed the bulkheads and all of the admiral’s furnishings, and they manned these guns and fired them. The beautiful “marble” tile floor was just painted canvas. There are a lot of interesting architectural details, which was one of the main reasons I wanted to build it. First of all, the walls are all paneled: I glued brass wire around the panels, which gave the impression of the gilt moldings.

The stern windows were a major effort, and one of the most worrisome parts of the project. The amazing aspect of those windows is that no two panes are exactly alike, because of the curve of the ship, and the way that the windows radiate outward. Obviously, the ones on one side are a mirror image of the ones on the other, but there are no two exactly alike. I found the easiest way to build them was with strip wood, first putting in the uprights and spacing them properly, and then adding the cross pieces. With the basic framework installed, it’s just a matter of adding narrower strips to build up the moldings. There’s a single piece of flexible clear plastic that goes across the back to simulate the glass.

In my research, I learned that the window seats were used as storage bins, so I had a wine bottle next to an open seat. I photographed a picture in a book to get the portrait of Lady Hamilton, which is the one Nelson took with him to sea. It may have actually been done after the Battle of Copenhagen, but it’s the best portrait of Lady Hamilton I could find, so I used it.

J.D. I love the wheel of Stilton and the bowl of walnuts on the dining table, and the dirty dishes piled up on the chest to one side.

S.P. I used the dirty dishes and silverware stacked up on the case that the admiral would have stored them in to show that dinner has already been completed. I found the dishes and silver in a dollhouse shop.

J.D. It seems to me that you’d learned a lot about the careful positioning of figures from “The Night Watch” and “The Admiralty Board,” because we can see almost everyone in the scene, even though half the people at the table have their backs to us. It had to take some trial and effort.

S.P. The problem was that Nelson is the smallest figure in the group, and if everybody were standing, drinking the toast, Nelson would be totally lost in the crowd. I came up with the idea of showing everybody rising as he proposes the toast. That way, the people in front of Nelson can conveniently be a little slower to rise than everyone else. The composition has a nice crescent effect, with the people still seated in the foreground, and people standing at the ends, but Nelson is the only standing figure, in the center.

One of the most interesting aspects of the figures is that I had to show Nelson smiling. Of course, there are no images of anybody from that period smiling, because having your portrait done was serious business. So I had to study the portraits of Nelson and try to imagine what he might have looked like when he smiled.

I think I enjoyed doing “To a Fair Wind… and Victory!” more than just about any diorama I did. It wasn’t so much that I loved the subject, but the challenge and satisfaction of doing all of the construction in the cabin. I was worried about how to do the chairs, because I’d never built anything more than just a simple stick chair, and these are obviously elegant pieces of furniture. I ended up soldering the chair together in brass., and I cut the peacock feather out of a rug beater I found in a dollhouse shop and soldered it into the brass chair back to provide the fancy fretwork. Then I cast up the chairs, so I was able to not only get a very fancy looking chair, but the number of exactly matching copies that I needed.

The sea green color of the walls, by the way, is mentioned in a number of contemporary accounts. And on the other side of the windows, there’s a black velvet wall with fiber optics poking through, representing the lights of the city of Copenhagen.

J.D. I never knew that: Andrew Wyeth bought this piece, and I’ve never seen the original, only the photos. When’s the last time you saw the box?

S.P. I saw it about ten years ago, when I was in Wyeth’s studio. I went to deliver “Barracoon,” and I did some minor repairs on a couple of his dioramas at the time: Dioramas do need occasional maintenance: Burned-out bulbs need to be replaced, and one or two small pieces sometimes have to be glued back in place again. Fortunately, I’ve never had to do a major repair on any of my boxes.