From Sheperd Paine: The Life and Work of a Master Military Modeler and Historian by Jim DeRogatis (Schiffer Books, 2008)

J.D. You’ve made a point of saying that you rarely took commissions, You’re your next box, “Doctor Syn,” was an exception.

S.P. But I also said I was happy to take suggestions! Andrew Wyeth’s wife, Betsy, contacted me and said he’d just finished this painting, and she thought it would make an interesting box for a Christmas present. I thought it would make an interesting box, too. Wyeth loves to joke that the painting is his only full-length self-portrait, because he’d gone in for hip surgery a year or two before that, and he’d asked them take a full set of X-rays at the time. The skeleton is actually based on those X-rays. The coat is based on a coat he actually owns: It’s an American naval officer’s coat from the War of 1812 period. The setting is a bell tower on their property, part of a small lighthouse complex on a small island in Maine. The tower has four sides and tapers inward on each side, rather like a pyramid: That inspired Wyeth to turn it into a naval cabin. He brought in some carpenters, and they put in the stern windows, the outside railing, the gun port, and the paneling. I had some photographs to work from, but I wanted to get a better sense for how the space felt, so Betsy invited me up to have a look at it. I was visiting my family on Cape Cod, and I drove up to Maine for the day. I saw both the tower and the painting, which was a great help once I started to work.

J.D. When you toured the bell tower, you and Betsy kept the secret so the gift would be a surprise?

S.P. I was “visiting friends in Maine and just stopped by”—that was the cover story—but I got to see the painting and all the components that went into it, including the uniform.

J.D. You’ve mentioned earlier that Wyeth had already bought several of your pieces. How did you meet him, and what was his interest in miniatures?

S.P. A few of his paintings featured toy soldiers, but he always liked miniature things of all kinds. If you read his book[1], his experiences growing up were a major influence on his work—he had a hundreds of toy soldiers at the time, and he still has many of them to this day.

J.D. Wyeth would attend the MCFA show at Valley Forge, take it in, and occasionally buy pieces—yours and others?

S.P. Right. The first time I met him was when I showed “Napoleon at the Tomb of Frederick the Great,” and he expressed an interest in it. I forget how we actually met up at the show. I think somebody said, “There’s someone interested in your box,” so they brought me over and introduced us, and he said, “I really like this. What do you want for it?” I quoted a price, and he replied, “I’ll take it.”

J.D. It’s fascinating that as an artist, Wyeth collected another realm of art that he never dabbled in.

S.P. Artists tend to stick to their milieu, and his is painting. Most artists have a few pieces of other artists’ work. Sometimes, it’s things they’ve admired; sometimes it’s things that just struck a chord with them, and sometimes, it’s things that were given to them.

J.D. Back to the box: I love the sense of the room flooding with sunlight.

S.P. The room is very bright when the sun comes through the windows, and that was how he painted it.

J.D. Was that difficult to capture in three dimensions?

S.P. No, not really; I think I did some supplemental painting on the walls. The only thing that’s not there in the painting is the wall on the right side; you don’t see that in the painting, but because the box is three-dimensional, I had to enclose the right side with something, and the wall seemed least intrusive. The wall was very plain, so I put in a couple of coat hooks. I asked Betsy, “What else can I put there—something personal?” So hanging on one of the coat hooks is a Swiss jacket that A.W. liked to wear. When she mentioned the jacket, I asked, “How about his paint box?” And she said, “Oh, yes, he’s got this battered old white tackle box that he carries his stuff around in when he goes out to paint.” So I put that in there as well.

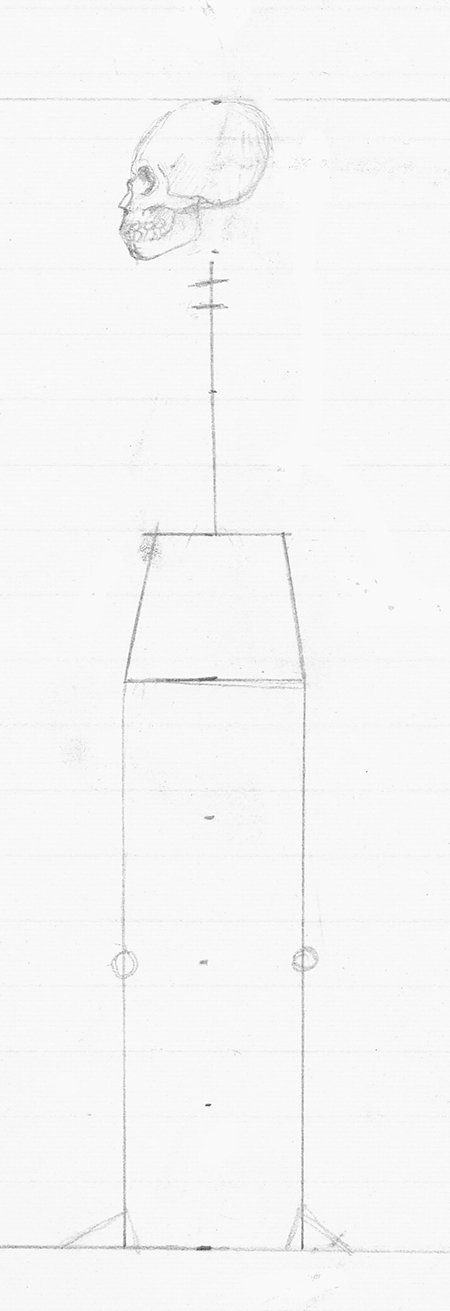

J.D. How did you do the skeleton?

S.P. It was built up on a wire form with A+B putty. For the landscape outside the window, I just painted a simple scene with some gray sea and gray sky.

J.D. Did you hear from Wyeth after he got his present?

S.P. Yes. One of the nice things about selling to the Wyeths was that whenever I delivered a diorama, he’d always give me a call and talk about how much he enjoyed it. It was very gracious of him, and I can’t express how much that meant to me. That was why I enjoyed selling to the Wyeths much more than, say, Malcolm Forbes.

J.D. Do you have any ideas about what Wyeth was saying in “Doctor Syn”?

S.P. A painting evokes a visceral response, not a logical one. Explaining a painting is like explaining a joke, and I think it was E.B. White who commented that explaining humor is like dissecting a frog—it can be done, but the patient never survives the operation.

“Doctor Syn” is like all of Wyeth’s paintings: It’s a realistic painting with strong mystic undertones. That’s the great characteristic of his work. You can never really explain a piece like that—it has an emotional impact that’s hard to define.

I took the box to the Chicago show after I finished it. I intentionally didn’t say anything about what it was about or who it was for. I wanted to put it out on display and see what kind of reaction it got. It’s interesting that only a few people asked, “What’s this thing about?” The box didn’t create an enormous stir in that respect—I think people just accepted it at face value. I never mentioned the Wyeth connection, because he hadn’t seen it yet, and I didn’t want it written up with his name associated to it.

J.D. If I can play the art critic for a moment, one of the things that strikes me about “Doctor Syn” is that while there is an element of beauty in the uniform and the militaria, and an appreciation for the echoes of glory they represent, there is also a sadness in the fact that the ultimate fate of so many soldiers is death—the skeleton. Does that relate at all to your own work? I mean, you are certainly not a gung-ho warrior type.

S.P. There’s an element of “the paths of glory lead to the grave,” but I wouldn’t want to speak for Wyeth as to why he does paintings. Again, I have a feeling that he makes the painting happen, and then lets the emotional content speak for itself. I suspect he doesn’t spend much time analyzing why he does what he does. I don’t think a lot of artists do—as E.B. White said, it kills the frog.

If you were asking me in a general way about my interest in military subjects, I’ve often wondered about that myself. I think it may be the drama: For better or for worse, war is the most dramatic activity people engage in, and it shows them at their best and at their worst. That’s why dramatists and filmmakers are so attracted to it. I’m essentially a dramatist, so I’m drawn to it, too. In earlier periods, of course, the colorful uniforms are part of the appeal, but I’ve done a lot of World War II subjects as well, so that can’t be the only reason.

That said, there are so many wars in history that I have plenty of subject matter already. I don’t need any more. I’ve read far too much about war to retain any romantic notions of what it’s like. Most veterans will talk about the funny things that happened to them, but they keep their nightmares to themselves. I know an armor officer who only models figures, and a former infantryman who only models armor—they don’t have any desire to model the things they actually saw in action—but most of the modelers I’ve known have no background in the military. I think that, like me, they’re drawn by the drama. It’s the personal experiences of those who were there, and the way the personalities of the people involved influenced the course of events that really gets me going. If you look at the books in my library, you’ll find most of them focus on the experiences of the people who were there, not the strategy and tactics.

E.L. Doctorow, who just published a novel on Sherman’s March to the sea[2], was asked in an interview about the difference between a history and an historical novel. He said, “A history tells you what happened, while an historical novel tells you what it felt like.” If there’s a thread that runs through my work, it’s that I try to show what it must have felt like, or what I think it felt like. Obviously, I wasn’t there, so I have to rely on my reading.