From Sheperd Paine: The Life and Work of a Master Military Modeler and Historian by Jim DeRogatis (Schiffer Books, 2008)

J.D. This brings us to your last boxed diorama, “Barracoon.” You did this one six or seven years after the Merrimac. Did Betsy Wyeth call you up again and commission it?

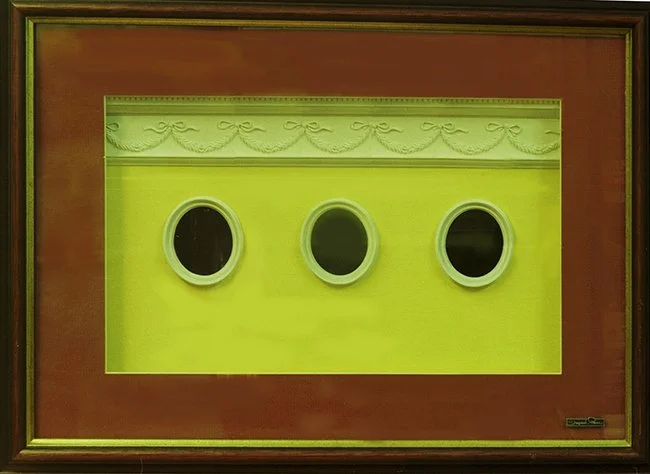

S.P. Yes, Betsy called me in 1997 about doing a box based on “Barracoon” for her husband’s eightieth birthday. The way it came about was interesting: She remembered “The Slave Trade,” and she thought I might be able to do a similar scene based on his painting, “Barracoon.” As we talking further over the next few days, she asked if I was familiar with the story of Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson. I said that I was, and she said, “If you remember, over Jefferson’s bed at Monticello, there is a small room called the wardrobe room, but the rumor was that Sally Hemings often slept there. Can we do something with that?” So I thought about it for a bit, and I realized that just doing the interior of the room wouldn’t really show anything, but that particular room had three oval windows for ventilation in the wall above Jefferson’s bed. I didn’t want to do the whole room, with Jefferson’s bed below that, which would have been a distraction. So immediately behind the frame on the front of the box is the wall with its three openings and the elegant moldings around them, and the classical frieze above that. You look through the openings and see the figure on the bed behind it.

J.D. So we have Sally Hemings reclining on her cot?

S.P. It’s a mystery, like Sally Hemings herself. There’s a black woman on a bed, and you can draw what conclusions you will.

J.D. This figure is larger than the others in your boxed dioramas, isn’t it?

S.P. Yes, that was almost nine inches tall. It was the only thing in the scene, and if it hadn’t been that big, you wouldn’t have seen anything.

J.D. Where did the title of your box and Wyeth’s painting come from?

S.P. A “barracoon” was originally a holding pen for slaves; that’s the title Wyeth put on his painting, so I just kept it. The original painting was just a nude black woman on a bed. Hemings’ story really hadn’t come out at the time he did the painting, but that of course is the central theme of the box, in spite of the fact that it was still a rumor—the DNA testing had yet to be done, and the physical connection between the Jefferson family and the Hemings family was yet to be established.

I liked the undercurrent of the box: the elegant Jeffersonian façade, and the scandalous yet touching scene hidden behind the windows.

J.D. You’ve set up an interesting point of view for this box: The viewer is outside, kind of floating in the air, and looking into the windows. The lighting is coming from the room?

S.P. Partially, but there are also some spotlights in the scene which illuminate it. If you look off to one side, you can also see the narrow curved stairs going down to Jefferson’s bedroom. I also added a chair and a candle off to the left, with a folded dress draped over the chair.

J.D. Did Wyeth enjoy this one as well?

S.P. He left me a wonderful telephone message, which I kept for a long time. I also received an e-mail some months later from one of Betsy’s assistants that read, “While up in Maine, it was wonderful to see how AW has your diorama displayed on an eye-level pedestal in his library. Without fail, every new person who enters their house is ushered into the library to view it—I’d say that project was quite a success!”

J.D. It’s quite a way to retire from doing boxes—with one final commission for a great artist like Andrew Wyeth. We talked a little about this much earlier, but I have to ask again why you gradually retired from modeling.

S.P. Well, as I’ve said before, I never took commissions, just suggestions. That wasn’t a matter of arrogance: I had learned early on that if your work is all on commission, you end up doing the same subjects over and over again, and you burn out on it very quickly. To me, the only way to keep it fresh was to do things that I wanted to do. Unlike some others, I never ran it as a business, but as a hobby that paid for itself. Obviously, I had to make enough money at it to pay my bills, but ultimately, I was a full-time hobbyist who sold his work to support himself while doing it.

J.D. I know there were a few great ideas for boxed dioramas that we’ve discussed, which you considered doing, but never completed. One was the scene in the Alamo with the Mexican troops discovering Mrs. Dickinson. There was also the lifeboat from the Titanic with two skeletons in it.

S.P. Some weeks after the sinking of the Titanic, a ship came across a lifeboat with two bodies, floating in the Atlantic. I thought I’d like to do that with two skeletons, one of a seaman in a White Star Line sweater at the tiller, and the other a passenger in a life belt and evening dress. As time has passed, I’ve learned more about that story, and the image I just described didn’t really square with the truth: The lifeboat turned out to be one of the canvas-sided collapsibles, and it was upside-down when they found it. I was intrigued by the Flying Dutchman aspect of the story, but the version I wanted to do would have called for more artistic liberties than I felt comfortable with, so I dropped the idea.

Another box I actually started was Napoleon’s campaign tent. It was the last one I was working on before I just sort of lost interest, and I never finished it. The plan was to do a night scene, with Napoleon in the blue-and-white-striped tent, planning the campaign with the maps spread around him, the marshals gathered around the table, and the sentries outside. I’d posed some of the figures, but never got any farther with it. I think the reason I eventually quit doing boxed dioramas was that the really enjoyable and creative part was planning it in my head. Once I knew what the thing was going to look like, all that was left was three or four months’ boring work. Now, as I said earlier, if there were some way I could plug a USB cable into my forehead and download a finished model onto the desk, I’d be doing them still!

J.D. So the painting and the sculpting stopped being fun?

S.P. Yes, because I really wasn’t learning anything—or I was learning relatively little. Back in the days when I wasn’t sure if I could do it, the challenge kept it interesting. You reach a point where you’re not doing anything you haven’t done before, you’re not learning any more, so it’s not fun any more.

J.D. It could be that the only way you suffered from having the privilege of being a professional modeler is that it was your job: For me, I don’t care how good or bad my modeling is, when I’m doing it, I’m not working, so it’s always fun.

S.P. When you are a professional, no matter how much you enjoy it, there are times when you don’t feel like doing it, but you have to do it anyway. Doing something you don’t want to do is the classic definition of work. Only a few people are lucky enough to do what they like for a living, and even fewer are fortunate enough to make so much money at it that if they want to take an eighteen-month break, they can. I never reached that stage, and I don’t know of anyone in the miniatures business that has, but if a successful musician, artist, or movie star wants to take a few months off to recharge their batteries, they can do it. The rest of us mere mortals have to work for a living.

J.D. Was your physical dexterity also a consideration as you grew older?

S.P. No, I could probably still do it now, but I haven’t tried. I’d done most of the things that I wanted to do, and I just gradually drifted away from it. I didn’t really make a conscious decision to stop; I just suddenly realized that it had been a few years since I’d done anything, and after a while, I realized that I really didn’t miss it. I enjoyed working on just about every piece I ever did, and when it stopped being fun, I simply stopped doing it.