This box is now in the collection of Joe Berton.

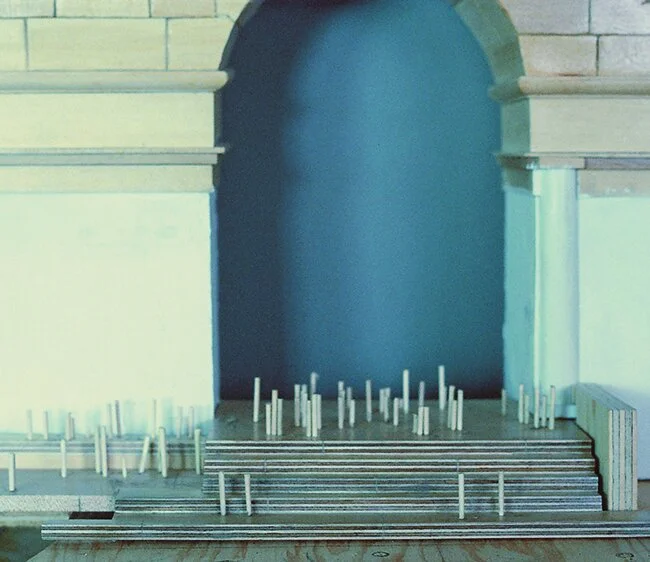

Above: The figures and the diorama in progress. Below: Additional detail shots.

SHEP’S NOTES ON THE NIGHT WATCH (THE MILITIA COMPANY OF CAPTAIN FRANZ BANNING COCQ)

I had wanted to do the Night Watch for about 10 years, but took that long to work up the nerve to attempt it. Normally, I have no interest in copying paintings or other forms of other people’s work but I found myself drawn to the Night Watch for a variety of reasons. First and foremost, I was interested in seeing what happened when the work was transferred to three dimensions: how this affected composition and the viewer’s impression of what was going on—would it be better, worse, or simply different? Second, there was the technical challenge of duplicating an acknowledged masterpiece: if it couldn’t be done well, it should not be tried at all. Technically, the greatest challenge was duplicating the lighting and the mood of the painting in a different format. Finally, there was the prospect of improving my style, perception, and technique; by studying the work of a great master hopefully something would rub off.

The original painting was commissioned by Captain Cocq as a portrait of his militia company to hang in musketeers hall, a common practice. What he got for his money was very different from the static group portraits done previously. Many figures are buried in the background and some are half-hidden or barely visible at all. Legend has it that the members of the Company were outraged by this treatment and that Rembrandt’s reputation went rapidly downhill after that, but this is not true. The members paid for the painting according to their position in it and there is no record of any dissatisfaction surrounding it. The reason it acquired the name “The Night Watch” is that it was hung for many years in the armory near the great fireplace and gradually acquired a coating of soot which darkened it substantially and dulled many of the colors. The painting is quite large (approximately 20 feet square) and when it was moved from the hall to the museum sometime in the 18th century a 18” were removed from left side so it would fit into the new space allotted for it. It was not until the restorations done during the 20th-century that all of the various lavers of varnish applied in the previous 300 years were removed in the painting revealed in all of its true glory. This is particularly true of the most recent restoration: colors never suspected all suddenly emerged and Rembrandt’s reputation as a colorist has been reevaluated.

There is an interesting controversy about the architectural escutcheon near the top of the painting, bearing the name of the company members. X-rays of the painting shows the architectural details underneath are fully detailed, and comparison with a contemporary copy done by another artist which omits this feature led to the belief that this was added a later date by someone other than Rembrandt. However, a similar X-ray made of the copy shows an escutcheon which has been painted out. Now nobody seems to know what to believe!

The first step in the research was to get a good reproduction of the painting. I studied several and quickly concluded that to do a major project of this sort justice I would have to make a trip to Amsterdam to study the original. which had fortunately just undergone extensive restoration. The painting is the pride of the Rijksmuseum, so I had no trouble finding it. When I finally sought it, I was literally awe-struck. The richness of the lighting I was prepared for, but the brilliance of the colors simply knocked me back on my heels. I stood and stared in an open-mouthed wonder for about half an hour. Shaking my head, I turned for the bookstore to see what the museum might have by way of reproductions and was bitterly disappointed. There were none that were even adequate, much less good; all the vibrant color, the rich texture of the light and dark. were simply washed out by the camera. Disappointed, I bought a set of slides and returned to the painting where I spent the next several hours taking detailed notes of colors and trying to fix a firm image an impression in my mind. The Prints and slides formed a technical reference but the visual impression carried back in my head would form the real basis of the diorama. Although I had determined long before that the purpose of the exercise would not be to duplicate the original tiny detail for tiny detail, I still felt that the posing and positioning of the figures was crucial if the composition of the original was to be preserved. Much care was therefore taken to arrange the figures precisely in relation to each other and the group as a whole.

The figures themselves presented a bit of a problem, since no two are dressed like and many of the details are lost in shadow. Much research was done, therefore, on 17th-century costume, a field in which I had little previous knowledge. Rembrandt was well known for his collection of exotic costumes and headdresses, and comparison of the figures in the painting with other contemporary works convinced me that Rembrandt outfitted his group with outlandish items from his own collection to dress up the piece. I searched for his other paintings to see if any of the items were duplicated there, but could not find any specific examples.

Since each costume was so different, each figure had to be designed and sculpted from scratch with a few common details being cast. Much care was taken with the rich embroidery and lush costuming of the central figures, particularly the Lieutenant. It is worth noting that he is rather short; like many men of small stature, he seems to dress to compensate for it, particularly when compared to the severely plain dress of the Captain, his superior.

An interesting enigma in the painting is presented by the musketeer directly behind the command group, who upon close examination is actually firing his musket, not twelve inches from the officers’ heads; another man is attempting to deflect the barrel. No one seems to have any idea just why this little detail was included, but the best guess is that this was an “in” joke for members of the company, immortalizing some long-forgotten parade ground folly. I did not include the puff of smoke in the diorama since it would have been far more noticeable in three dimensions and would raise more questions than it answered.

Lighting was the most challenging part of the actual construction. Rembrandt used the light in varying degrees of brilliance to highlight and emphasize his figures and the relative values of this light are critical to the composition. After much experimentation, a series of twelve spotlights were used to carry the effect properly a frustrating experience that took two weeks. The final effect, however, is very close to the original and well worth the effort.

When the left side of the painting was cut off in the 18th century, three figures were removed from the composition. I was able to restore these by referring to the contemporary copy made before the alteration. I also had to add extra figures in the wings on the right side since these were implied but not visible in the painting but would definitely be seen in the diorama.

What was the ultimate result of this experiment? I learned that Rembrandt’s composition holds up as well in three dimensions as it did in two, and that the design gets fresh new life and interest in the new format. The dramatic effect of the light and composition, while diminished somewhat by the smaller size, has a jewel-like quality that is appealing on its own, if in a different way. I think I learned more as an artist from this piece than any previous one. I was forced to learn to direct and control light to greater effect, and it became a much more important factor in my work that had been in the past. I was always fascinated with the use of light, but now I could use it more effectively.

From Sheperd Paine: The Life and Work of a Master Military Modeler and Historian by Jim DeRogatis (Schiffer Books, 2008)

J.D. The next box is incredibly ambitious: “The Night Watch,” after the painting by Rembrandt.

S.P. It was ambitious; I was always looking for new challenges. In this case, I wondered how the painting would change if it were shifted into three dimensions—how would the composition, concept, and storytelling change? When I finished, I concluded that Rembrandt designed a good diorama, because the composition holds up extremely well, and the space adds a certain dimension to it that it doesn’t have in a flat form. It was quite a project to work on just to find that out, and I would never do one like that again. I proved the point, and that was enough for me.

J.D. You’ve said that you generally weren’t fond of copying paintings.

S.P. No. People had done plenty of models copying paintings, and it’s a fun exercise once in a while—particularly if you’re exploring territory that hasn’t been explored before—but other than that, all you can ultimately produce is a second-rate imitation of a first-rate piece. But the thing that intrigued me about “The Night Watch” is that everybody is familiar with the painting in a vague sort of way—the shapes, and what a couple of the central characters are doing—but they have no real idea what’s going on in the scene, or how many other figures there are in the painting and what they’re up to. So I wanted to put it into three dimensions to see how this would change the perception of the figures and the way they interrelate with one another, and also how the composition would change when transferred from two dimensions to three.

My original idea with “The Night Watch” was to do it in flats, because I had seen flats catalog with the two central figures, but I later discovered that the manufacturer had only made those two central figures, so I abandoned it. Some years later, it occurred to me that this would be a interesting project in 100mm, and a real challenge, but it was a technical challenge, rather than an artistic one.

J.D. That’s because, once again, everything was scratchbuilt: the figures, the weapons, the pikes….

S.P. I didn’t have much choice. The matchlock muskets were the hardest. When I did muskets—and, thank God, I only had to sculpt a couple of muskets in my career—I started by turning the metal barrels on a lathe, so they were properly tapered. Then, I would build up the stock with A+B putty. You could only rough-shape the stock while the putty was soft; the final shaping was done by sanding and cutting the putty after it hardened. Once the stock was ready, the next step was to add things like the barrel bands, again sanding them square and flat after the putty hardened. The final stage was adding the lock, ramrod, and other details. When I had a complete musket, I’d cast copies in white metal.

J.D. Do you think you succeeded in adding new light to what’s happening in the painting? I’ve got to confess, I’ve never really understood the scene.

S.P. To a certain degree, when you look at the diorama, you don’t have much of an idea of what’s happening either, except that there is a lot of activity going on. The painting was commissioned as a portrait of a local militia company. The traditional format for these group portraits was to line everyone up like a team photo. This was pretty boring, so Rembrandt decided to try a less formal approach and have something going on in the scene. The practice was that people paid according to the prominence of their position in the painting: The guys in the background didn’t pay as much as the ones in the front. Rembrandt put some of them so deep into the background that they must not have paid much at all! The two men in the foreground were the captain and the lieutenant, and they were pretty wealthy: They could afford it.

The actual title of the painting is “The Militia Company of Captain Frans Banning Cocq,” and he is the man in black at the center of the picture. The lieutenant who’s next to him is actually the figure you notice most, simply because he’s the one who has the fancy costume—your eye is drawn to him immediately. While this was a company of Dutch militia in the 1640s, Rembrandt took a lot of license with the clothing. Military units didn’t have uniforms at the time, but some of the clothing could charitably be described as “vintage.” The drummer on the right side, for example, is wearing landsknecht dress that had gone out of fashion about a hundred years before. Rembrandt loved fancy clothes and helmets, and he had a fairly elaborate prop shop, so I think a certain amount of the costumes came from there. Except for the two central characters, I’d be surprised if many of the people are wearing their own clothing. I remember looking through some of his other paintings to see if any of the same helmets or accessories turned up in other paintings, but I didn’t find any.

J.D. You went to see the painting before doing this box, right?

S.P. Yes, I actually went to Amsterdam to see the painting, and I’m very glad I did, because the colors in the original painting are so different from the reproductions in books. By the time the printer gets one set of colors right, the others are off. There are purples and reds in this painting that never show up in the reproductions.

I also discovered while I was there that the painting was cut down in size many years ago, and several figures on the left side disappeared. Another artist’s copy of the painting before it was cut still exists, and I was able to restore these figures to the composition.

J.D. Was using another artist’s palette a challenge for you as a painter?

S.P. Yes, it was. I had to rein in my own imagination, because I was constantly referring back to the original painting. The challenge, of course, was copying it as closely as possible, not only in terms of the colors, but also the figure posing and placement. The figures had to be placed exactly right in relation to each other. I kept moving the figures back and forth until they were positioned exactly as they were in the painting. One-sixteenth of an inch one way or the other could make a difference—the positioning was that precise.

The figures were all pinned into place, so I kept drilling holes and moving the figures around until each was in just the right place. When I got the holes I wanted, I’d circle them to differentiate them from the other holes. I didn’t worry about how many there were, since it was an easy matter to fill the unwanted holes with toothpicks; clip them off at the base, and sand the surface smooth. If you look at the in-progress pictures, you see can a bunch of toothpicks sticking up out of the base. Each toothpick represents a mistake!

J.D. With 100mm figures, this had to be a big box.

S.P. Well, I’ve always liked my dioramas to be about the size of a breadbox. This was a big breadbox, but it wasn’t enormous. I do remember that about that time, I bought a new car, and I remember taking some dimensions of the back seat to make sure this box would fit into it for the trip to Philadelphia!

J.D. So, ultimately, this box was about really testing your modeling chops, in terms of painting and sculpting.

S.P. And the lighting: There were a lot of spotlights; I think the final number was twelve. Most of them were on individual dimmers, so I could raise and lower the relative brightness of different parts of the scene.

J.D. You must have gotten really good at electronics by this point.

S.P. Not at all. If I had been good at electronics, I could have figured out the resistance on the potentiometers versus the voltage of the bulbs and saved myself a lot of experimentation. I didn’t do any of that; for me, it was all trial and error. I got a bunch of resistors, and tried different combinations until they worked right. But those brass tube spotlights worked so well, and they were easy to make: They telescoped in and out, which meant I could control not only the brightness of the light, but how much area it covered. And here, some spotlights focused on individual figures.

J.D. The spotlights involved one length of tube inside another, with the bulb in the center?

S.P. Right. The one tube would slide back and forth, just like a trombone. I just came up with that; necessity is the mother of invention.

J.D. Did you have to sculpt a lot of new heads to capture Rembrandt’s likenesses?

S.P. Well, my stock company appears in the background, but by then, I had expanded the company quite a bit by adding to it with each diorama. I devoted a lot of attention to the central figures, because they needed to match as closely as possible the painting, but again, I took a lot of the repetitive details—the blousy breeches, the shoes with bows on them, some swords, muskets, and halberds—and cast them up.

J.D. How did you do the building? It’s really impressive.

S.P. It’s all made out of basswood. Basically, it’s a plywood wall with thin basswood blocks for the individual stones. I carved each individual stone, and then glued them in place on the wall. The escutcheon next to that archway was sculpted in A+B.

There’s an interesting mystery about the escutcheon: It does not appear in the early copy made of the painting, so for many years, scholars believed it was a later addition to the original. Then, they X-rayed the copy and found that the escutcheon was there, but it had been painted over! Now, no one knows what to believe.

J.D. How long did this box take?

S.P. The whole project was about five months’ work, and it was the only thing I was working on at the time. I may have taken a break for an auction figure or other minor diversion, but there was no other major project underway at the same time.

JIM’S NOTES ON RESTORING THE BOX IN 2023

The inner tray removed. Damn, that thing is HEAVY! There are A LOT of 100mm metal figures on there and all of the scenery is built of half-inch plywood.

Shep wasn’t kidding about not worrying about what isn’t seen. The back of the flag is not only not painted, but not even finished!

For purposes of our ongoing lighting/reveal discussions, the scene is set back almost a full six inches from the viewing window!

What came out of the box. I used all of Shep’s brass-tube spots, because I wanted to keep the LEDs focused on where he’d had the incandescent bulbs shining, but there was no need for the telescoping pieces. He’s also wrapped all of the automotive bulbs in paper to make for a tighter fit in the tubes, but the paper had singed from the heat—NOT a good idea! And damn, that transformer! Amazing the box never caught fire. After much study of photos of his box, and the painting, I went with warm LEDs as replacements, the better to capture the light both masters wanted.

The outer box, nicks and scratches repaired. Damn, it‘s MASSIVE! That’s a 75mm figure for scale!

Above: The tray back in place (a very, very tight fit!), and the reveal in place with new LEDs. Below: The dimmer Jim installed to control the brightness of the LEDs.

Below: Joe Berton’s brother, Dave, delivered the box after Jim and he picked it up from Beloit Auction and Realty (which sold off the Ralph Koebbeman collection), and the box at Joe’s place. Jim notes that cell phone pictures make the LEDs seem “whiter” than they actually look in person, where he tried to match the warm, slightly yellow light of Shep’s (and Rembrandt’s) original painting, despite the night-time setting.