The battle of the Monitor and Merrimac as most often depicted—“like two mechanical robots floating around and shooting at each other,” as Shep said. This painting was in the collection of Ralph Koebemann.

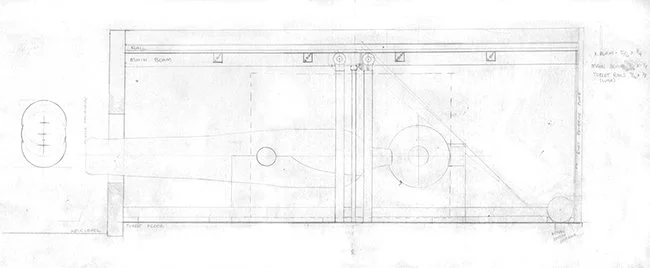

Shep’s cross-section plan of the turret of the Monitor.

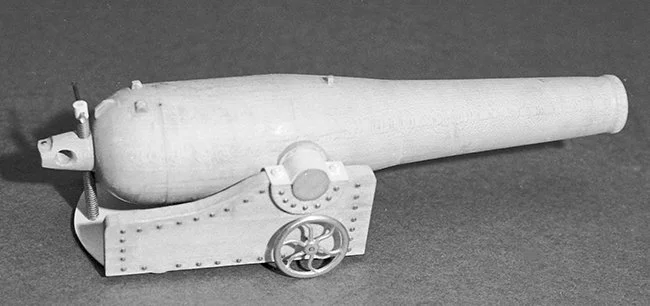

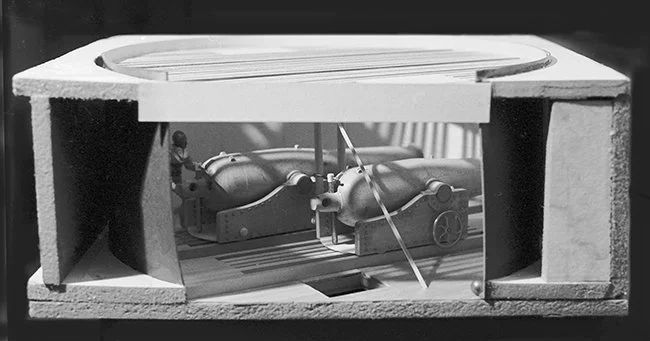

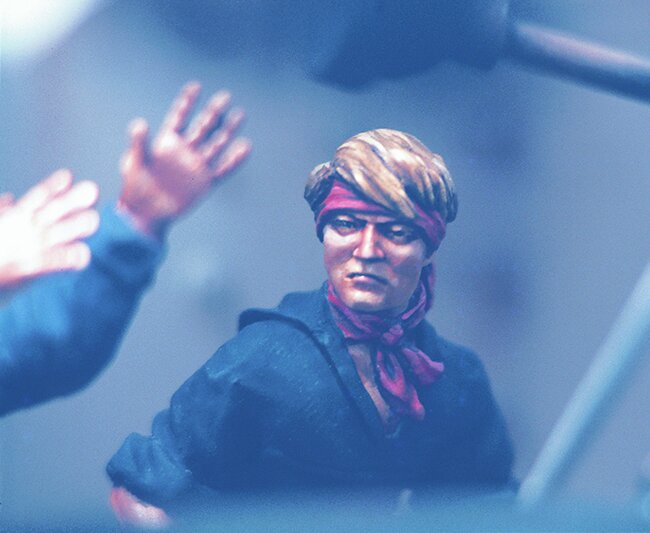

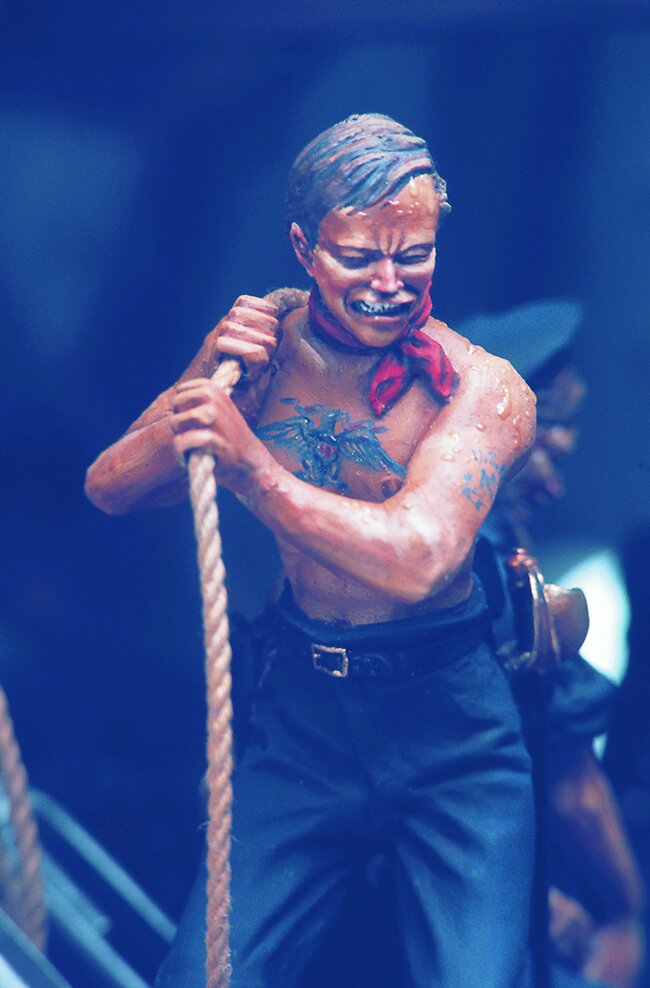

Above: Several shots of Shep’s diorama in progress. Below: details from the finished diorama.

Shep’s notes on the diorama

This was my first serious boxed diorama. I was drawn to subject for number of reasons. First. nearly everything I had ever seen depicting the famous battle between the Monitor and the Virginia (Merrimac) was from the outside, giving the impression of two robots fighting, with no sense at all of the men inside the machines. Second, the subject seemed ideally suited to a box and no one had ever tried it before. Third was the technical challenge of duplicating and researching the interior.

Since little information was published on the Monitor at that time, research consisted primarily of examining closely the few drawings of the Monitor still surviving and comparing these to the more numerous in-detail drawings of her successors to discover just how things worked. I also corresponded with a number of experts on subject, including some who had taken part in the dive to the wreck off Cape Hatteras.

The circular design of the turret proved to be an unusual and challenging design feature for a diorama, both technically and compositionally. Pure construction projects are always fun for me, less draining and demanding than figures, yet challenging in their own right. This was my first effort at extensive modelling in wood, a material that I have since used regularly, and I was pleased to discover that I can manage it quite easily.

From Sheperd Paine: The Life and Work of a Master Military Modeler and Historian by Jim DeRogatis (Schiffer Books, 2008)

J.D. The next box you did (in 1976) was much more ambitious than your first, the small Historex scene you called “Idylls of the Voltigeur.” Tell me about “In the Turret of the Monitor.”

S.P. I’d always been fascinated with the Monitor, and I thought, “This is a good subject for a box.” I was going to do it in 54mm, because that’s the only scale that I had ever seen boxes done in, at least in the hobby world. Pitman’s boxes were bigger, but Ray Anderson’s boxes were all 54mm Historex conversions. I wanted to do the Monitor because I was interested in the way it was enclosed in a round space, and I thought it would be a dramatic scene to do, but I also realized that I was going to have to scratchbuild all of my figures. And I realized, too, that because the dimensions of the turret were set, the dimensions of the box were also going to be set, because it depended upon the dimensions of the turret. I quickly discovered that I was going to wind up with a viewing window about two by three inches, which was really too small—you’d almost have to close one eye to look into it. So I thought, “Well, if I’m going to have to scratchbuild the figures anyway, I might as well do them in 100mm, and get a bigger viewing window as well.”

J.D. Even in 1/18 scale, that was still a pretty small opening for the box.

S.P. Yes, it was about four by six inches.

J.D. It’s hard to get a sense of that, looking at the pictures, because it’s such a dramatic scene. Why were you interested in the Monitor?

S.P. Well, I’d always been interested in the Civil War, even though I’d done relatively little modeling work with it. The pictures you always see of the battle between the Monitor and the Merrimac show them from the outside, and they look like two mechanical robots floating around and shooting at each other, but I was interested in the story inside. That was where the people were, and I wanted to show what it was like inside one of those ships during the battle.

What most people don’t realize about the Monitor was that it was a totally revolutionary warship: It is estimated that there were more than forty patentable inventions involved in her construction. Another significant fact is that the Monitor sailed into battle directly from the construction yard in New York. There had been no time for sea trials, and the crew had never fired the guns until they went into action for the first time. They must have been really nervous, going into action in an untried vessel against a Confederate ironclad that had had terrorized the whole U.S. Navy, sinking or disabling three Union warships in an afternoon. They had no way of knowing whether their revolutionary armored turret would stop Confederate shot. They later reported that being inside the turret when shot hit the outside was like standing inside a giant bell, and I think the only injury sustained in the turret was a man leaning against the turret wall when it was hit: The concussion temporarily knocked him out.

J.D. Tell me about the research, Shep. How the heck did you figure out what the dimensions of the Monitor were?

S.P. Well, the dimensions are well-known from contemporary plans. Fortunately, through my connections with the Company of Military Historians, I got some great help from Ernest Peterkin, who was doing a lot of the original research on the Monitor, because they had just discovered the wreck off Cape Hatteras. They couldn’t get into the turret at the time, but he had found a lot of the original drawings that had been used in its construction; he said that some of these drawings still had the workmen’s footprints on them! Now, of course, they’ve brought the turret up, and they found a few things that we were wrong about, but I think we got pretty close. The major difference was that there were some shields that were installed over the bolt heads on the side of the turret. We knew about the shields from the plans, but the feeling at the time was that these were installed after the battle.

It was fascinating, researching the Monitor. The discovery that they used railroad rails for the overhead I found interesting, and the recoil control mechanisms were ingenious. Space in the turret was severely limited, so the recoil system consisted of a series of iron plates hanging below the carriage between the rails of the slide it set on. A large wheel on the side of the carriage tightened a screw, which clamped the rails and plates together, and the friction reduced the recoil to a few feet.

J.D. As we saw in Chapter Six, you’d done 100mm sculpting before on individual figures and small vignettes, but this was the first time you did a large group, right?

S.P. Yes. As I said before, one of the things I did to cut down the amount of time was to cast up a lot of the parts I needed: Not only cutlasses, pistols, and cartridge boxes, but also the arms, legs, and heads for the figures. For example, there were several sets of legs in bellbottom trousers; a basic torso in the sailors’ jersey; a nude torso that was used on a number of the figures, and nude and sleeved arms. And, again, this was the beginning of what became my stock company of actors: about four or five heads that I used in the scene.

J.D. I’ve always loved the kid who’s bringing up gun powder from below. Come to think of it, he’s very reminiscent of the powder monkey on the gun deck of the Victory…

S.P. It’s the same head.

J.D. That kid got around!

S.P. The one on the Victory was his grandfather!

A number of the figures in the Monitor are personalities. Dana Greene is the lieutenant firing the gun; he commanded the turret and actually aimed and fired every shot. The only way the men could see out of the turret was through the small holes in the port stoppers, and they quickly discovered that the steam engine that controlled the rotation of the turret didn’t allow them to make any fine adjustments. In the end, they’d just start the thing in motion, and since they had have no idea what direction the turret was pointing when they started, Greene would just stand and wait with his hand on the lanyard until the enemy ship came into view through the gun port.

J.D. How did they light the real Monitor, and how did you light the box?

S.P. The real Monitor had the railroad rails above, with about an inch of space between each rail, and that created a grating which allowed daylight to pass through. The top of the turret was essentially exposed to the elements: It was awfully wet when it rained. So I lit the box from above, and that was one of the things that really intrigued me about the scene: the patterns created by the daylight coming down through the rails. The lighting in this box was very simple—just a pair of nine-inch fluorescents—with none of the spotlights I used later on.

J.D. How did you sell this box?

S.P. I had two people who were interested in it: One was Ralph Koebbeman, and the other was Malcolm Forbes[1], so I held a telephone auction for it. Ralph, of course, was intimidated by the fact that he was going into a one-on-one auction with one of the richest men in the country, and I think he was even more astonished when he beat Forbes out! Obviously, Ralph wanted it more than Forbes did.

In May 2023, the collection of Ralph Koebemann was sold at auction by Beloit Auction and Real Estate. As Shep’s artistic executors, Joe Berton and Jim DeRogatis bid on and won several of his box dioramas. The lighting had burned out on all of them, and some needed other minor repairs. Here are Jim’s notes on the restoration of the Monitor.

The turret of the Monitor removed from the box, and with the slatted round roof taken off. Shep fitted the roof so it just sat in the turret above the iron walls.

The powder monkey outside the box for the first time since 1976; you kind of had to finagle him out of the hatch to remove the inner-scene tray. Shep had just secured the block to the bottom of the inside of the box with masking tape, and it was rotting away (yikes!). Thankfully, neither he nor any of the other 13 figures were scratched or damaged.

The only signs of lead rot in this box were on the cannonballs. I removed the ones that were easy to access (the walls were not removable, so everything else had to stay put), then cleaned them up per Joe’s suggestion: removing the rot, priming with Humbrol enamel, and repainting with enamel. (The ones I couldn’t remove got the same treatment as best I could.) On the right: other bits and bobs that were loose and rattling around, now secured back in place. Below: The inside of the box, all cleaned up and with new LED fixtures in place. Shep had covered the entire box interior with aluminum foil, presumably to protect from the heat generated by the two fluorescent fixtures he used for illumination. (You’ll see he put two vents in the back wall for the same reason.) I replaced his fixtures with three 12-inch warm white LED under-cabinet lights after researching the most reliable brand. When I repaired the Victory the first time for Dan Bird, I used a different brand, and those somehow shorted out in Dan’s wall after his death. These are the same I used to repair the Victory again for Bill Neustadt, and they come with a nifty handheld dimmer. I removed the foil, once I concluded it wasn’t for lighting purposes. Sorry, Darryl, but I didn’t save it! I also had to resecure the glimpse of water—which looks like a photo of Lake Michigan by Shep!

A view of the turret interior from above. You’ll see lots of holes in the deck in the back, where Shep played with positioning the figures; quite a task with those walls in place!. Below: the turret back in place. Shep used a sheet of frosted glass over the Monitor’s slatted roof to diffuse the lights. I added a light yellow theatrical gel on top of it to get a bit more of a filtered sunlight effect. LEDs don’t cast shadows in quite the same way fluorescents do, but I did get them on the cross beams. The powder monkey is now held in place with industrial-strength Velcro. Shep once saw it in use in one of my boxes and said, “I wish I’d thought of that!” So, here you go, Shep.

The Monitor box, refinished, and holding a place of honor in Joe Berton’s collection. What a joy! You’ll see I’ve been removing the glass from the matts; it’s trashed, beyond clean-up. I’ve come to the conclusion that the glass isn’t really needed, and only adds unwanted reflections and glare, but if Joe wants to replace it, I’ve advised him to get the good museum glass cut to size by his favorite framer, as I’ve done on some of my boxes in the past.