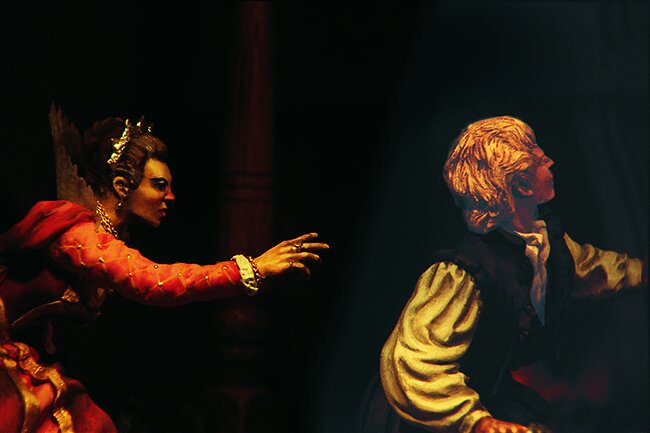

SHEP’S DIORAMA DISPLAY TEXT

ACT III SCENE IV

Enter GHOST.

Hamlet: A King of shreds and patches!

Save me, and hover o’er me with your wings,

You heavenly guards! What would you, gracious figure?

Queen: Alas he’s mad!

Hamlet: Do you not come your tardy son to chide,

That, laps’d in time and passion, lets go by

Th’ important acting of your dread command? 0, say!

Ghost: Do not forget! This visitation

Is but to whet thy almost blunted purpose.

But, look, amazement on thy mother sits.

O, step between her and her fighting soul.

Conceit in weakest bodies strongest works.

Speak to her, Hamlet.

Hamlet: How is it with you, lady?

Queen: Alas, how is’t with you,

That you do bend your eye on vacancy

And with th’incorporal air do hold discourse?

Forth at your eyes your spirits wildly peep,

And as the sleeping soldiers in th’alarm

Your bedded hair, like life in excrements,

Start up and stand on end. 0 gentle son,

Upon the heat and flame of thy distemper

Sprinkle cool patience. Whereon do you look?

Hamlet: On him, on him! Look you, how pale he glares!

His form and cause conjoin’d, preaching to stones,

Would make them capable.

Do not look upon me,

Lest with this piteous action you convert

My stern effects; then what I have to do

Will want true colour, tears perchance for blood.

Queen: To whom do you speak this?

Hamlet: Do you see nothing there?

Queen: Nothing at all, yet all that is I see.

Hamlet: Nor did you nothing hear?

Queen: No, nothing but ourselves

Hamlet: Why, look you there! Look, how it steals away!

My father, in his habit as he lived!

Look, where he goes, even now, out at the portal!

(Exit Ghost.)

From Sheperd Paine: The Life and Work of a Master Military Modeler and Historian by Jim DeRogatis (Schiffer Books, 2008)

J.D. You went back to your literary bookshelves for the inspiration for “A King of Shreds and Patches (The Ghost of Hamlet’s Father).” I’m guessing you did this one for the challenge of the ghost?

S.P. It’s all about the ghost! I wanted to do a three-dimensional ghost that you could see through—a transparent figure that was completely round, and not just a flat, two-dimensional image. The trick of using the half-silvered mirror and the reflection of the ghost in the mirror is what appealed to me about it. The ghost you see is not a figure, but a reflection of a figure

J.D. How did you work out how to do it?

S.P. I’m not sure. I have a vague recollection that this technique may have been used onstage for some of the ghosts in stage productions.

J.D. What is a half-silvered mirror?

S.P. It’s a mirror that has only half the normal amount of silvering; it’s often referred to as one-way glass. It’s what they use in the police stations during lineups, so that the witness can look through the glass and see the suspects in the lineup without the people in the lineup seeing the witness. As you look into the scene and through the archway, you can see the stairwell, and the mirror is between the archway and the stairway wall. The figure of the ghost is behind the tapestry to the right, facing the rear of the box. What you’re seeing in the half-silvered mirror is a reflection of the figure of the ghost, which is all painted white.

There are obviously lights in front of the mirror, but there is also a light behind the mirror, which illuminates the back wall. To understand how a half-silvered mirror works, think back to the lineup at the police station. The reason the suspects can’t see the witness is because the witness is in a dark room and the suspects are in a bright room. This means that essentially, all they see is the mirror, but the witness in the dark room looking into a bright room can see everything in the other room. It’s all a matter of the relative brightness on either side of the mirror. I had the box set up with dimmers, so that I could raise the lights in the room and lower the lights behind the mirror, controlling exactly how transparent the ghost was.

J.D. So no matter where you displayed the box, we could see the ghost?

S.P. Right. I could arrange it so that the ghost always had the proper degree of transparency. The whole idea of it is that you have to be able to see the back wall through the ghost in order for the illusion to work; otherwise, it’s just a reflection of the figure. The bottom of the figure was painted black, so the ghost seems to float in midair.

The hard part of working with mirrors, particularly in a scene like this one, is working with them so that they don’t reflect anything you don’t want the viewer to see. This is often a lot harder than it sounds Angling the mirror is very important.

J.D. Tell me about the sculpting.

S.P. Hamlet’s mother is mostly A+B, but if you look closely at her, it’s the powder monkey’s face from the Monitor and the Victory! You only see it in profile, so you don’t notice it unless you know, which is the reason I got away with it, and with the hairdo and the dress, nobody thinks of the powder monkey.

J.D. Were people surprised by this one when they saw it?

S.P. No, I don’t think so. Peter Twist had done one some years before, of a different scene with a ghost up in the battlements, but he had used a solid figure and put it behind a piece of frosted glass, so it was a very different effect from this. What appealed to me was the idea of doing a transparent ghost. If I had to do it as a solid piece, I don’t think I’d have ever done it. The goal was to carry the special effects further than they had gone before.

J.D. How did you do the tapestry?

S.P. There were actually two tapestries, depending on which set of photographs you look at. For the first one, I used a color Xerox of a tapestry, but later on, I found a real piece of tapestry that worked perfectly.

The other thing that’s worth mentioning about “The Ghost of Hamlet’s Father” is that a modeler with a theatrical background pointed out that Polonius is actually killed much earlier in the scene, long before the ghost makes its appearance. My feeling about it was that Polonius didn’t go anywhere—Hamlet doesn’t haul him away until the end of the scene—and while the posed figure of Hamlet certainly suggests that he has just finished dispatching Polonius, that’s not necessarily true.